By Omar Khoury

In 1917, British author Israel Zangwill pithily remarked: “‘Give the country without a people,’ magnanimously pleaded Lord Shaftesbury, ‘to the people without a country.’ Alas, it was a misleading mistake, for the country holds 600,000 Arabs.” Along the same lines today: “‘Give a country to a people,’ magnanimously pleaded the leaders of several Western nations, ‘but subject to certain conditions.’ Alas, it appears to be a misleading mistake, for conditioning recognition while a people’s self-determination is being denied runs afoul of international law.”

In the past few months, a growing number of Western states—including the United Kingdom, France, Australia, Canada, Portugal, and Belgium—have added their voices to the 150+ member chorus of countries that recognize the state of Palestine as a sovereign entity. But the Western melody sings to a different tune, for the decision to recognize comes with strings attached. These countries have pledged to recognize a Palestinian state only if certain conditions are achieved, including a democratic reform of the Palestinian Authority, a requirement to host general elections, the exclusion of Hamas as a political or governing party, the release of remaining Israeli hostages, and the demilitarization of a future Palestinian state. Portugal and Belgium further required any recognition of a Palestinian state to manifest through a collective, multi-national agreement.

Some argue that recognition at this time is merely a hollow spectacle uttered by cornered-in politicians aimed at placating the growing domestic discontent among the agitated electorate in Western nations. But the acts of recognition coming from Israel’s staunchest defenders are undoubtedly historic. These countries appear to recognize the legitimacy of the political aspirations of the Palestinian people in areas over which Israel has asserted ultimate sovereignty and maintained a military occupation since 1967. Moreover, the recognition of a Palestinian state contradicts the party platform of one of the governing parties of Israel, which categorically rejects a Palestinian state and declares that “between the [Mediterranean] Sea and the Jordan [River] there will only be Israeli sovereignty.”

Recognition, however, may ultimately not bear any sweet fruit. Western nations, by placing the onus for action on an occupied people, are disregarding the long-standing denial of Palestinian self-determination. These imposed conditions for the recognition of a Palestinian state do not advance international peace and security because they do not adequately respond to the sustained and ongoing breach of international peace and security arising from the Israeli military occupation. The imposition of conditions for recognition erodes the core rights of the Palestinian people to self-determination and may violate jus cogens pertaining to the “inherent” state right of self-defence, as described in the UN Charter. While these nations are understandably attempting to manage an internationalized conflict, conditioning recognition of a Palestinian state without addressing the underlying breaches of peace and security imprudently places international politics far above international law.

Self-Determination and Recognition Under International Law

The right to self-determination is the “fundamental” right of a people to choose their own political status and realize their destiny as a people. State recognition is the formal acknowledgment by an existing state(s) that a political entity representing a people meets the criteria for statehood and is considered a subject of and a sovereign under international law. It is a declaration that an international person exists. The formal act of recognition confers rights and obligations to the new state or government, including the ability to enter into treaties and conventions with other states, to participate in international organizations, to access international judicial and arbitral bodies, and to permit diplomats to enjoy immunities and privileges.

Although international law lacks explicit guidance on the recognition of states, the Montevideo Convention of 1933 (the “Convention”) is the prevailing authority and outlines the typical criteria for statehood. Article 1 of the Convention defines a state as “a person of international law [that] should possess … (a) a permanent population; (b) a defined territory; (c) government; and (d) capacity to enter into relations with the other states.” But where the Convention employs the mandatory “shall” and “will” in the succeeding provisions, the word “should” in Article 1 suggests that the existence of a state is not contingent upon the fulfillment of these criteria.

Indeed, Article 3 of the Convention provides that the “political existence of the state is independent of recognition by the other states.” It further establishes that a state or entity has certain rights, such as “the right to defend its integrity and independence, to provide for its conservation and prosperity, and … to organize itself … [e]ven before recognition.” As such, recognition of a state’s right to exist is not necessarily gatekept by the recognizing state(s).

The Convention espouses what is known as the “declaratory” theory of recognition, which holds that a state exists even without recognition, the act of which is merely a “declaration” of the preexisting political situation. This has become the prevailing view in international law over the competing “constitutive” theory, which mandates that a state first be recognized by other states before receiving the formal right to exist as an international person.

The “declaratory” theory is premised on a foundational principle of international law: the right of a people to national self-determination. UNGA Resolution 1514 expresses the broad scope of this inviolable right: that “[a]ll peoples have the right to self-determination; by virtue of that right they freely determine their political status and freely pursue their economic, social and cultural development.” More than sixty years later, the General Assembly passed UNGA Resolution 77/207 in 2022, “[r]eaffirm[ing] that the universal realization of the right of all peoples, including those under colonial, foreign and alien domination, to self-determination is a fundamental condition for the effective guarantee and observance of human rights and for the preservation and promotion of such rights.”

Conditional Recognition in Theory and Practice

Self-determination is one of the few rights actually enshrined in the UN Charter. This distinction informs the Article 6 of the Convention’s determination that recognition of a state is “unconditional.” But significant tension manifests in the interplay of a people’s right to self-determination and the recognition by other states of a people’s collectively determined political entity.

While self-determination is a bedrock principle of the United Nations, member states often condition recognition of new states upon international legal compliance, such as implementation of democratic reforms and commitments to international laws and norms. In its 22 July 2010 Advisory Opinion on whether the Kosovo’s unilateral declaration of independence violated international law, the International Court of Justice noted that “it has not been uncommon for the Security Council to make demands on actors” or to place “conditions for [the] achievement” of a people’s recognized independence and self-determination. Many European states in the 1990s, for example, required emerging states in the aftermath of the Soviet Union’s collapse to commit to nuclear non-proliferation, progress towards minority rights, and respect for borders before they were recognized as international persons. Even today, the Taliban occupy Afghanistan’s seat at the United Nations, but the Islamic Emirate remains unrecognized by virtually every member state in the organization, with states potentially changing course where substantial steps are undertaken to democratize governance and to protect minority rights.

Thus, while technically superseded by the right to self-determination, the practice of conditional recognition stubbornly persists in international relations. It is no doubt a politicization of the right to self-determination. States generally argue that imposing prerequisites on statehood is both pragmatic and necessary to foster international stability, prevent the emergence of failed states, and ensure respect for democratic norms and peaceful coexistence. By setting benchmarks such as the protection of minority rights or the establishment of transparent or democratic governmental institutions, proponents contend that conditioning recognition on commitments to international norms not only creates new states but also responsible members of the global community.

States have even flatly refused to recognize a situation where, through its emergence, a state violated international custom. When Southern Rhodesia unilaterally declared independence in 1965, the UNSC passed Resolution 216 “call[ing] upon all States not to recognize [the] illegal racist minority regime in Southern Rhodesia and to refrain from rendering any assistance to [the] illegal regime.” In Resolution 217 eight days later, the Security Council explained that its decision stemmed from the “racist settler minority[’s] … usurpation of power” that “constitute[d] a threat to international peace and security.” It is not apparent from the Resolutions whether members of the international community would have recognized Southern Rhodesia if the government undertook drastic reform or made commitments to particular social groups. But setting aside the arguments of whether Southern Rhodesians qualified as a “people,” the Security Council declarations are significant in the explicit circumscription of the otherwise supreme international legal right of a people to self-determination.

Conditional Recognition of a Palestinian State

Today, Western nations are committing to the recognition of a Palestinian state so long as a future Palestinian state meets certain conditions. Those conditions include a democratic reform of the Palestinian Authority, including a requirement to host general elections, the exclusion of Hamas as a political or governing party, the release of remaining Israeli hostages, and the demilitarization of a future Palestinian state. Some nations also demand recognition to unfold through a collective, multi-national agreement. And others would (begrudgingly) permit the existence of a rump Palestinian state—but only on Israel’s sufferance. So the arguments go, conditional recognition would encourage reform of the Palestinian authority, would address international security concerns, and is in line with historical precedent.

Aspirational as they are, however, some of the conditions demand of the Palestinian people their capitulation. Conditioning recognition on reform of the Palestinian Authority and demilitarization when Palestinian self-determination is itself being denied by an occupying power fails to preserve international peace and security. The imposition of conditions on an occupied people undermines the legitimacy of self-determination, potentially constitutes unlawful intervention, and conflicts with inherent state rights like self-defense. By requiring the fulfillment of conditions from an occupied people, and not from the occupying power that has effectively stayed Palestinian self-determination by instituting a decades-long military occupation and annexing Palestinian land, conditional recognition of the state of Palestine ultimately frustrates the spirit of the Charter.

First, imposing conditions for Palestinian statehood may constitute unlawful intervention into the internal affairs of Palestine. Article 8 of the Convention expressly reads that “[n]o state has the right to intervene in the internal or external affairs of another.” But the process of granting, withholding, or withdrawing recognition of state authority over a particular territory or population “profoundly shapes” the character of the new state and its international standing. However much noble democratic aspirations should be upheld, the requirement that the (albeit corrupt) Palestinian Authority hold immediate elections in order for Western nations to recognize a Palestinian state is difficult to reconcile with the already well-established recognition of the Palestinian Authority as the de-facto and legitimate government of the state of Palestine by over 150 nations. Notwithstanding foreign occupation, the state of Palestine nominally satisfies the traditional criteria for statehood under its current government. To require it to hold snap elections where elections would not restore peace and security in the West Bank or Gaza would be to impose a condition that drastically changes the internal political situation but fails to account for reality—where the occupation, ongoing violence, and lack of meaningful autonomy renders the prospect of free and fair elections almost unattainable. This demand effectively shifts the burden for political legitimacy onto a population being chronically denied basic prerequisites for self-determination, while absolving the occupying power of responsibility for creating an environment conducive to democratic governance.

Second, the requirement of the demilitarization of a true Palestinian state conflicts with another right enshrined in Article 51 of the UN Charter: the right of self-defence. Demilitarization goes much further than the requirement of a “demilitarized zone,” such as the demilitarization of the Sinai peninsula. Rather, complete demilitarization of a Palestinian state would vitiate the inherent right of a people to self-defense, especially in a context where ongoing threats to civilian safety persist, including Israeli settler violence and state-sanctioned appropriations of Palestinian land. By insisting on total demilitarization, Western nations as external actors are interfering with a future Palestinian state’s ability to protect itself from external aggression or to rationally respond to security challenges. Rather than fostering international peace and security, this stipulation perpetuates vulnerability and dependency on an occupying power. Moreover, conditioning recognition on demilitarization sets a problematic precedent within international custom because it authorizes the relinquishment by a state comprised of a people of core rights of statehood.

Conclusion

Recognition of a Palestinian state is understandably fraught given the unique historical and political complexities at play. But that does not relieve states from their obligations to abide by international law and respect international rights. Recognition must respect the sovereignty of the aspiring state, especially where its people have historically been denied statehood. Conditional recognition advances these principles where the conditions are voluntarily accepted by the prospective state or aspire to protect minorities and democratize governments. In the case of Palestine, however, conditional recognition undermines sovereignty through coercion and conflicts with jus cogens.

Nations must critically reckon with whether conditions placed on Palestinian recognition truly advance peace and security or whether they otherwise undermine the very rights they purport to protect.

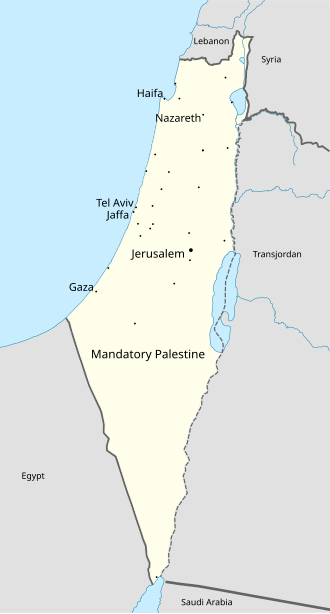

Credit: map of Mandatory Palestine, the territory placed under British administration between 1920 and 1948, and under the terms of the League of Nations’ Mandate for Palestine after 1922 @ Wikipedia