By Jessica Drew, a PhD Researcher and Graduate Teaching Assistant in the School of Law, Criminology and Policing, Edge Hill University, UK.

Some small island states are ‘disappearing’.[1] The rising sea is set to take their territories. The at-risk states include the Maldives, Kiribati, and Tuvalu.[2] Whether these states will lose their statehood as a result of their loss of territory is a question which has divided scholars of international law.[3]

Loss of statehood would come with extensive consequences. States have rights that other bodies do not. For example, states enjoy sovereignty over their natural resources, only states can invoke the jurisdiction of the International Court of Justice (ICJ), or legitimately use force.[4] The cessation of statehood could create a stateless population, generating questions around migration and the feasibility of en masse relocation.[5]

The Montevideo Convention codified the requirements for the conception of statehood.[6] Article 1 sets out that states must have: ‘a permanent population’; ‘a defined territory’; ‘government’; and ‘capacity to enter into relations with the other states’.[7] The at-risk states will no longer have defined territories or permanent populations and therefore will no longer meet the Montevideo criteria. Previously, states have become extinct through events such as conflict and state succession. However, the complete loss of territory is unprecedented in contemporary international law.[8] A ‘legal no-man’s land’ ensues.[9]

There are compelling theories to support the continuance of the statehood of states with disappeared territories. One primary argument looks to state recognition and the way in which a state comes to be. There are two conflicting theories on the creation of states.[10] One accepts legal principles as the requirements for statehood, the other adopts a more political approach.

The declaratory theory provides that ‘statehood is a legal status independent of recognition’.[11] Thereby, a polity has statehood if it fulfils legal criteria even if it is not yet recognised by other states. The legal criteria are found within the Montevideo Convention and constitute ‘the most widely accepted formulation of the criteria of statehood in international law’.[12] This theory appears to prevail in practice.[13] For the disappearing islands, the declaratory theory could mean that when they lack territory, they fail to meet the criteria codified in the Montevideo Convention and as a result, they will suffer de facto loss of statehood. However, the disappearing islands have sovereign personalities in international law. This is not easily revoked.

The second theory, constitutive theory, poses that statehood is contingent upon recognition.[14] Proponents of this theory argue that a polity must be recognised as a state by other states to be considered as such. Without recognition, statehood cannot be. It is independent of the fulfilment of legal criteria.

The simplicity of these theories is not wholly aligned with the concept of statehood in practice. In practice, it is unclear whether the theories on statehood relate only to the creation of states or also to state continuity.[15] The ICJ has cited a ‘fundamental right of every State to survival’.[16] Even the Montevideo Convention accepts that state recognition is irrevocable, but this is further complicated by contrary state practice.[17]

There are circumstances where the normative criteria of statehood have not been continuously upheld, and yet, statehood has endured. For example, the Vatican lacks a permanent population and governments in exile continue to be recognised despite lacking effective government, although Montevideo does not stipulate whether a government must be effective or not, just that a ‘government’ is required for statehood.[18] Exceptions such as these demonstrate that a state’s failure to meet the criteria codified in Montevideo is unlikely to automatically lead to the loss of its statehood. Therefore, for the disappearing islands, the loss of statehood due to loss of territory may not be so simple. It is also unlikely the international community would revoke recognition of the sovereignty of small island states against their will.

Despite this, scholars have offered various solutions to safeguard the statehood of disappearing islands. These solutions exist on different points of a spectrum between solutions which solely answer the question of statehood and those which answer the question of migration. Some answer only the former, some the latter, others answer both and the solutions range from the normatively acceptable to the more conceptual and ‘radical’.[19]

Continued recognition of a small island state despite its loss of territory is one normatively acceptable solution.[20] This solution is aligned with the constitutive theory on statehood and precedential state practice. This may be the natural future of the disappearing island states should the Montevideo territory criterion not automatically cause loss of statehood.

There is no minimum amount of territory required for a state. At present, Montevideo can be interpreted as requiring ‘some physical territory’ but no baseline is prescribed.[21] Placeholding is presented as a solution which maintains physical territory and therefore upholds the defined territory criterion. It involves the construction of a ‘sovereignty marker’.[22] This may take the form of a lighthouse or a similar construction that would remain within the territorial jurisdiction of a small island state.[23] This is aligned with the normative principles of statehood and would safeguard state continuity when natural territory disappears. Neither continued recognition or placeholding answer the question of migration but would ensure the continuation of sovereignty.

Some solutions would facilitate en masse relocation and continued statehood. These include the acquisition of land elsewhere through the cessation of land from another state or the purchase of territory.[24] It is unlikely states would voluntarily cede territory to another, and the purchase of territory is a function of private international law which would not transfer sovereignty, so the issue of continuing statehood would remain.[25] Another option would be a disappearing state locating and occupying unclaimed land.[26] However, this is also unlikely as all territory is considered to be under some form of state control.[27]

A solution adopted by the Maldives is the creation of artificial islands. If constructed within a disappearing state’s territorial waters, an artificial island may safeguard statehood.[28] The alignment of this solution with the current normative framework on statehood is disputed.[29] However, should a flexible approach be embraced in the exceptional circumstances of the disappearing island states then artificial islands may work in international law. Although, beyond the legality of artificial islands, their substantially high cost and the environmental damage resulting from their construction make them inappropriate for universal implementation.[30]

A novel, creative solution, probably unfeasible within the current bounds of international law is deterritorialised statehood.[31] This takes continued recognition and enhances it to a practical format involving governance over a population which has been diffused globally.[32] It is likely that many disappearing states will eventually end up in a deterritorialised form, with their populations dissolved globally.[33] This solution is not without difficulties. A significant risk to the statehood of the disappearing states is long term ‘state death’.[34] A key question is whether a state lacking territory will inevitably disappear despite continued recognition.[35] This is often overlooked when solutions are proposed.

Arguably, through time and generations deterritorialised statehood will reduce these states to nothing more than administrative embassies. The likelihood of this may be aggravated or mitigated with the chosen method for the relocation of populations. Current approaches to relocation, such as the introduction of working visas, create a trickle effect whereby populations gradually relocate away from their small island state of origin. The shape of migration from disappearing states may impact a state’s claim to sovereignty, a dwindling population can upset a government’s effectiveness.[36]

A reformist solution is the provision of remedial territory to the disappearing islands from high greenhouse gas emitter states.[37] The small island states are responsible for only a small proportion of global emissions. Yet they are set to lose their territories, an effect which is due, in part, to global emission-creating activities. There has been discussion surrounding responsibility and accountability of high emitters of the international community. Unfortunately, however, this is likely to be out of reach. It would prove very difficult to establish a forum and jurisdiction for such proceedings.[38] If successful, then would come the major barrier of enforceability.

Without intervention or adaptation, lack of territory may lead to the loss of statehood for the at-risk small island states. There is division over the exact outcome due to the lack of clarity surrounding the territory criterion. Politics, state practice, migration strategies, and the general belief held internationally on the disappearing states will determine the outcome of their statehood.

The solutions disappearing states wish to use to preserve their statehood and national identities should be unequivocally the choice of the island states. However, the process of maintaining the statehood of disappearing states is heavily reliant on international cooperation and coordination. There is time before the disappearing states become uninhabitable. This can be used to explore potential options available and to further prepare robust procedures, supported by the international law on statehood.

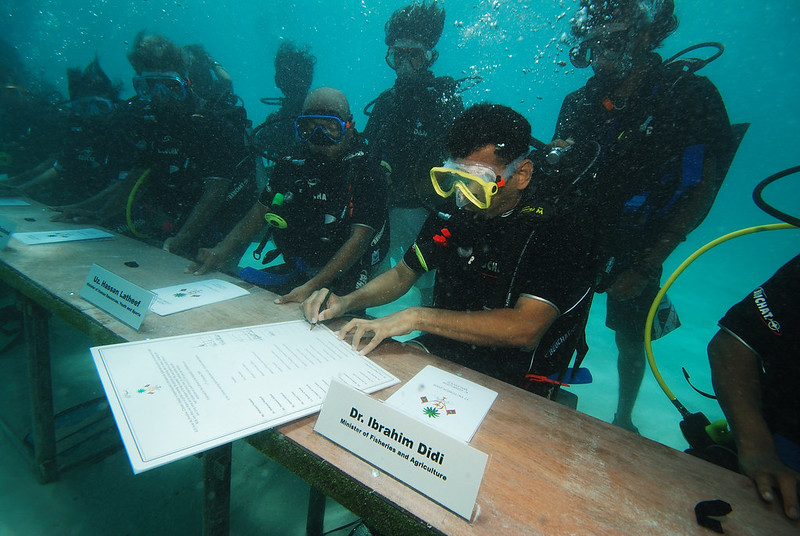

Photo: Underwater signing, Maldives. Credit: Mohamed Seeneen / Climate Visuals

[1] Sumudu Atapattu, ‘Climate Change: Disappearing States, Migration, and Challenges for International Law’ (2014) 4(1) Washington J of Environmental L and Policy 1, 3.

[2] Jane McAdam, ‘‘Disappearing States’, Statelessness and the Boundaries of International Law’ in Jane McAdam (ed), Climate Change and Displacement: Multidisciplinary Perspectives (Hart Publishing 2010) 107-108.

[3] James Ker-Lindsay, ‘Climate Change and State Death’ (2016) 58(4) Survival 73, 81.

[4] Emma Allen, ‘Climate Change and Disappearing Island States: Pursuing Remedial Territory’ (2018) Brill Open Law 1 <https://doi.org/10.1163/23527072-00101008> accessed 3 July 2023.

[5] McAdam (n 2) 112, 118.

[6] Montevideo Convention on the Rights and Duties of States (signed 26 December 1933) 165 LNTS 19 (Montevideo Convention) art 1; Ryan Mitra and Sanskriti Sanghi, ‘The Small Island States in the Indo-Pacific: Sovereignty Lost?’ (2023) 31(2) Asia Pacific L Rev 428, 429.

[7] ibid.

[8] Allen (n 4).

[9] Maxine Burkett, ‘The Nation Ex-Situ: On Climate Change, Deterritorialised Nationhood and the Post-Climate Era’ (2011) 2 Climate L 345, 350.

[10] Mitra and Sanghi (n 6) 434.

[11] James Crawford, The Creation of States in International Law (2nd edn, OUP 2006) 4.

[12] Malcolm Shaw, International Law (6th edn, CUP 2008) 198.

[13] Michael Gagain, ‘Climate Change, Sea Level Rise and Artificial Islands: Saving the Maldives’ Statehood and Maritime Claims through the ‘Constitution of the Oceans’’ (2012) 23(1) Colo J Intl Envt’l L & Pol’y 77, 88.

[14] Crawford (n 11) 20.

[15] Ori Sharon, ‘Tides of Climate Change: Protecting the Natural Wealth Rights of Disappearing States’ (2019) 60(1) Harv Intl LJ 95, 98; Lilian Yamamoto and Miguel Esteban, ‘Alternative Solutions to Preserve the Sovereignty of Atoll Island States’ in Lilian Yamamoto and Miguel Esteban (eds), Atoll Island States and International Law (Springer 2014) 212.

[16] Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons (Advisory Opinion) [1996] ICJ Rep 226, 263.

[17] Montevideo Convention, art 6; Hersch Lauterpacht, ‘Recognition of States in International Law’ (1944) 53(3) YLJ 385, 389.

[18] Sharon (n 15) 102.

[19] Ker Lindsay (n 3) 79.

[20] ibid.

[21] Abhimanyu George Jain, ‘The 21st Century Atlantis: The International Law of Statehood and Climate Change’ (2014) 50(1) Stanford J Intl L 1, 6.

[22] Ker-Lindsay (n 3) 78; Lilian Yamamoto and Miguel Esteban, ‘Vanishing States and Sovereignty’ (2010) 53(1) Ocean and Coastal Management 1.

[23] ibid.

[24] Yamamoto and Esteban (n 15) 178.

[25] Jain (n 21) 9-10; Crawford (n 11) 717.

[26] Island of Palmas Case (United States v The Netherlands) (1928) Scott Hague Law Report Rep 2d 83.

[27] Jain (n 21) 47.

[28] Gagain (n 13) 82.

[29] United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (adopted 10 December 1982, entered into force 16 November 1994) 1833 UNTS 397 (UNCLOS) art 60(8) and 121(1)-(3); Allen (n 4) 5.

[30] South China Sea Arbitration (Philippines v China) (2016) PCA Case No 2013-19 (South China Sea) para [983]; Simon Mundy and Kathrin Hille, ‘The Maldives Counts the Cost of Its Debts to China’ Financial Times (London, 11 February 2019) <https://www.ft.com/content/c8da1c8a-2a19-11e9-88a4-c32129756dd8> accessed 10 September 2022.

[31] Burkett (n 9); Allen (n 4) 23.

[32] ibid 346.

[33] Yamamoto and Esteban (n 15) 197.

[34] Ker-Lindsay (n 3) 94.

[35] Ori Sharon, ‘To Be or Not to Be: State Extinction Through Climate Change’ (2021) 51(4) Envtl L 1041, 1045-1046.

[36] McAdam (n 2) 129.

[37] Allen (n 4) 12

[38] ibid 20.

The existential crisis created by climate change, global warming and rise in sea levels for the island states, cities and their inhabitants is unprecedented. It is high time international community either redefined or broadened the notion of an independent and sovereign State. The traditional definition of State mentioned in the Montevideo Convention needs to be revisited in the enlightened interest of all.

LikeLike